First, for what is essentially a strategy paper, the New Economic Model is a hefty read. Not so much for the length (it runs to 209 pages), but the density – there are a lot of proposed changes, with some uncontroversial while others pretty incendiary. The next three months are going to be very interesting, as what we have now is just the strategy framework, with details on the implementation due in June/July to coincide with the unveiling of the 11th Malaysia Plan.

To be honest, some of the proposed policies are rehashed from the 8th and 9th Malaysia Plans, which indirectly points to the failure to actually realise these development goals. More than a few are actually covered by other policy documents such as the National Innovation Model and the National Higher Education Plan. But a few of course are a completely radical departure from business as usual, that give this document the right to carry the title “New”.

I find the language of the document itself pretty refreshing. If you’ve ever read through any of Malaysia’s Economic Reports or BNM Annual Reports, you’ll now what I mean – the NEM doesn’t pull many punches. A few examples:

...The difficulty of starting businesses, enforcing contracts, and dealing with construction permits — as just specific examples — bear testimony to a sluggish bureaucracy no longer fit for purpose in a fast-moving world.

...Some have suggested that a formal minimum wage might be helpful to cushion workers against such shocks or downturns. The NEAC strongly believes this would be a wrong approach and in fact could exacerbate the situation by reducing competitiveness and reducing employment opportunities.

...Resistance is likely to come from the business community including protected industries, employers of foreign labour, licence holders, beneficiaries of subsidies, and experts at doing business the old way. Some segments of the rakyat who no longer qualify for government subsidies and grants might react strongly, and those that have enjoyed secure jobs and a stable lifestyle from protected firms may feel threatened. Both these groups might then turn to their political representatives and politicians may then attempt to lobby and water down the needed measures. The resistance from these vested interest groups must be dealt with fairly and transparently, following genuine consultation.

There’s enough here to make virtually every special interest group unhappy. The unions won’t like the proposed changes to make hiring and (more importantly) firing easier, nor with strong dismissal of the minimum wage idea. Employers are already unhappy about the restrictions on hiring foreign employees, and the new pension schemes – they’re going to be even less happy with the proposal to put foreign workers on equal legal footing with domestic workers. Staff at GLCs must be wondering what the future will hold for them.

And more than a few are going to be up in arms over the roll back of affirmative action.

This is the biggie, and the true litmus test for the success of this administration. If Najib can pull this off, he may be remembered as the greatest PM in Malaysia’s history…or its most vilified (fingers crossed, I hope this doesn’t descend into violence). I have to say, the delays in announcing the NEM and hints dropped by other ministers had me wondering if this wouldn’t be watered down in some way – but the NEM was unequivocal about this issue.

It went even further than I thought it would, with means-testing instead of a race-based policy. I thought the former was very likely and more desirable from a social welfare perspective, but I didn’t suspect dropping the latter. Ironically, this places the NEM as the direct spiritual descendent of the 1970 New Economic Policy, a back to basics move so to speak. While the NEP is often used as justification for Bumiputera preferment and ended up being used that way, the original intent was for poverty eradication irrespective of race. It just so happened that most Bumiputeras were below the poverty line in 1970, hence the blanket race-based approach. I haven’t outlined my thoughts on the NEP in this blog, but you can find most of my thinking in the comments of this post on SatD’s blog.

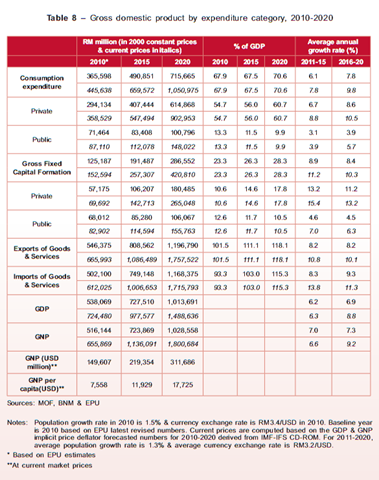

As far as the targets go, I don’t think them too demanding:

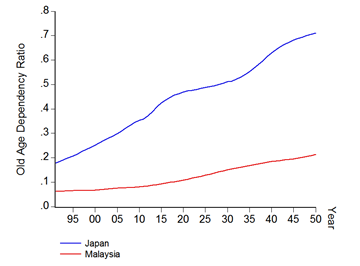

We’re looking at 8.8% nominal GDP growth over the next decade, which funnily enough isn’t actually much different from what we did over the last decade. I continue to believe that it’s more important to focus on the type of country and economy we want to be, rather than on getting to high income status. We’ll get to the latter soon enough, as much from demographic factors as anything else.

I don’t know if I want to get into more specifics of the NEM just now, especially since we’re still looking at debating the merits of each proposal over the next three months. Nor am I yet going to comment on any of the announcements made during the PM’s speech relating to EPF, Khazanah or Petronas. There will be ample space and time for debate on these issues as they arise in the public sphere.

On a personal note, I’m chuffed to find an ex-colleague in the NEAC office – and my Masters supervisor on the Advisory Group. It’s a small world.

Technical Notes:

- Prime Minster’s Speech at Invest Malaysia (pdf link)

- New Economic Model for Malaysia, National Economic Advisory Council