Just over a year ago, I did a blog post on different types of recessions and the policy responses appropriate to both. Thinking about the IPI this morning and overcapacity in electricity generation and manufacturing prompted me to relook this issue.

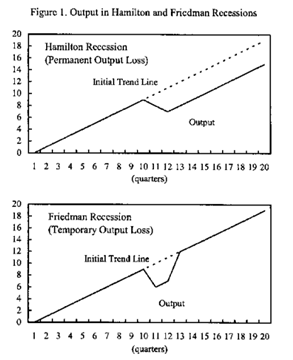

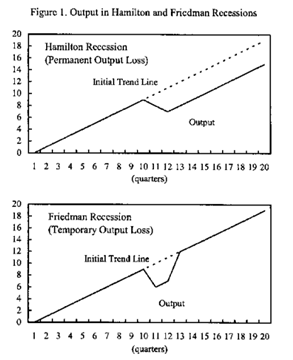

To recap, a Friedman recession is one which is associated with an increase in the output gap, which is the difference between potential output based on labour and capital capacity to produce. The Hamilton recession is where potential output itself is dropping, which signals a permanent loss in output.

The difference between the two can be illustrated by the following figure:

I thought at the time that this downturn would turn out to be of the Hamiltonian type, which requires an active fiscal policy response beyond automatic stabilizers, even if some of that effort leaks out through higher imports. A Friedman recession can usually be handled by judicious use of monetary policy alone.

Of course, it’s really hard to tell in the heat of the moment which particular situation you happen to be in, particularly with data lags of 2-3 months for some of the critical data. This is especially true since the defining variable – the output gap – is unobservable and has to be estimated.

Past experience and research output helps guide policy of course, so in the spirit of contributing to that, I’m going to take a rough and ready approach to answering this question. We’re still not quite out of the woods yet in terms of both global and Malaysian economic recovery, so this should be taken as just preliminary, not definitive.

In other words, it’s Friday evening, this is a purely academic exercise, and I’m amusing myself.

First, I’m going to take a purely stochastic (probability-based) non-model based approach i.e. I’m not even going to bother with estimating the output gap (that’s beyond my knowledge at the moment).

Many economic series typically display a consistent pattern – you can take advantage of this fact to model them stochastically by just following a mathematical rule (otherwise known as a “data-generation process” or d.g.p.) to define the shocks. Most follow a d.g.p. that approximates to a 1-lag auto-regressive pattern (denoted as AR(1)), which also implies what’s called trend-stationarity. In other words, if you take away the trend of an AR(1) time series, it will look like a random walk – the detrended time series is randomly distributed around a mean of zero.

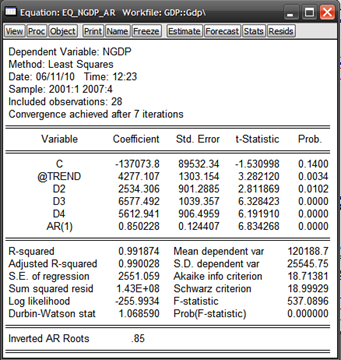

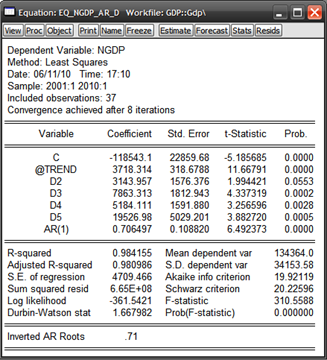

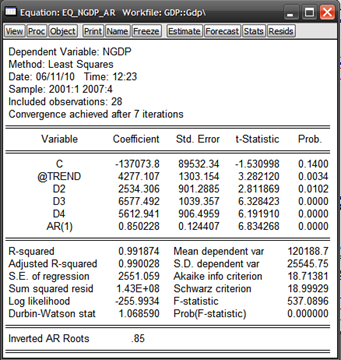

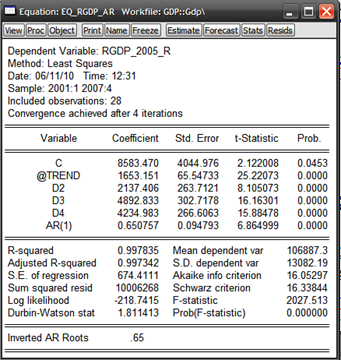

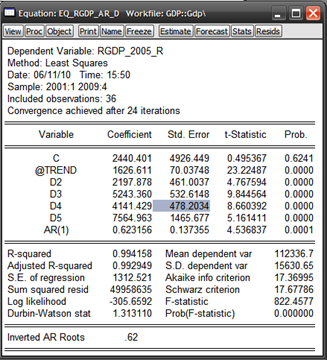

I’ve taken both nominal and real quarterly GDP for Malaysia for the sample period of 2001:1-2007:4 to illustrate what I mean. The regressions look like this:

rGDP = constant + @trend + d2 +d3 +d4 +AR(1)

nGDP = constant + @trend + d2 +d3 +d4 +AR(1)

…where @trend represents a linear time trend; d2, d3 and d4 are the seasonal dummies for 2Q, 3Q and 4Q of every year; and AR(1) is the autoregressive term.

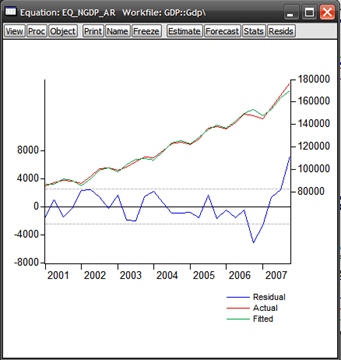

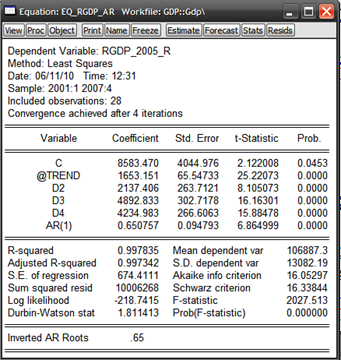

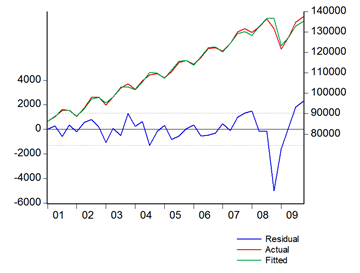

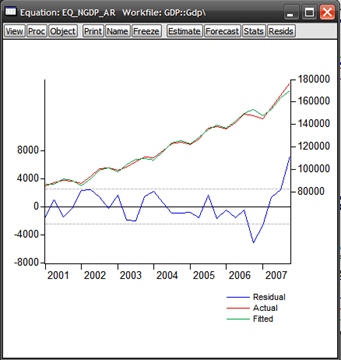

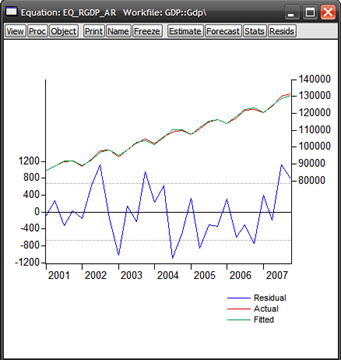

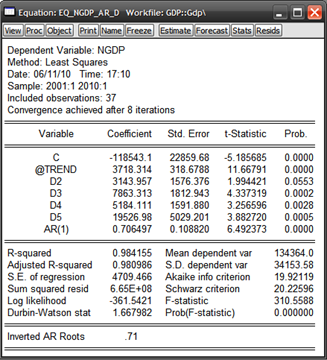

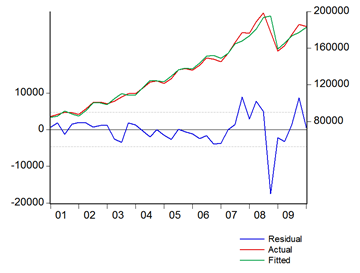

Running the regressions yields:

All the explanatory variables are almost all statistically significant at the 95% level (Prob. values below 0.05), diagnostics all check out ok, and we have a very, very close representation of the actual time series (very high R2). It’s interesting to note that the error values (residuals) for the rGDP model are an order of magnitude smaller than that of the nGDP model.

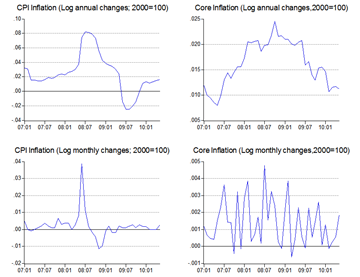

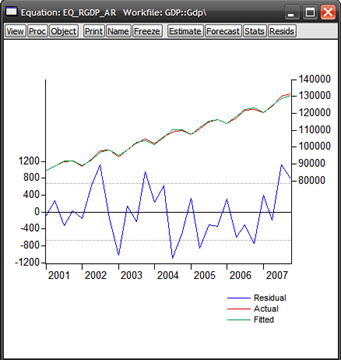

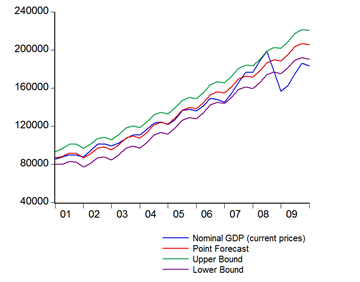

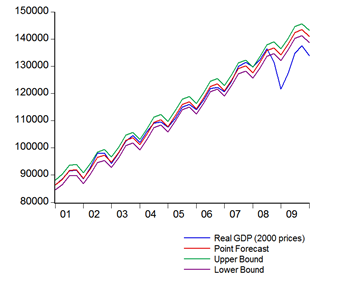

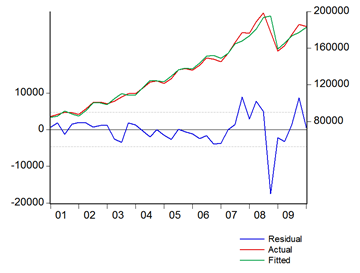

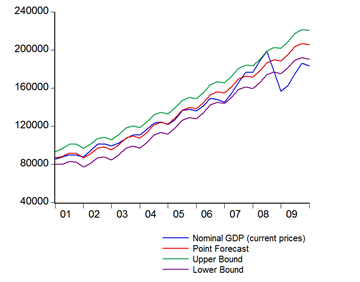

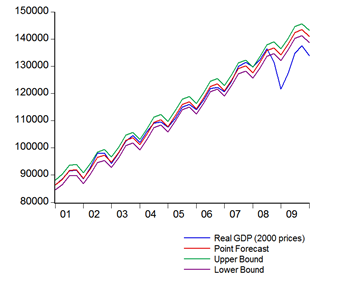

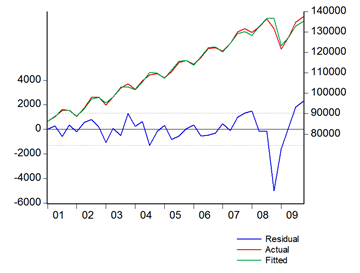

Now that I have a baseline model(s), I can use historical values of GDP to forecast future values of GDP. This doesn’t turn out so well as a pure forecasting exercise because we had the commodity boom in 2008, and fell into recession in late-2008 to 2009 (out of sample forecast: 2008:1 to 2010:1):

Now you can partially see why so many forecasters and policymakers got caught out by this recession, and why so many risk models in the financial sector failed. The drop in output far exceeds the potential band of possible outcomes implied by historical data. That argues for a more structurally based approach to forecasting, though to be fair, that hasn’t fared much better in the present crisis.

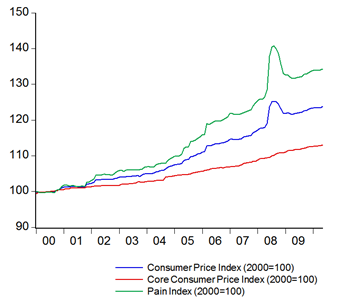

But I digress. For today’s post, this failure serves my purpose pretty well – the forecasted level of GDP can be taken to represent potential output, and I now have a probability based measure of the output gap. I can’t obviously make a determination on whether there was a permanent drop in potential output, which defines a Hamilton recession, but what I can do with this is to ask (statistically speaking) whether there has been a change in the path of economic growth, which is almost (but not quite) the equivalent.

Specifically, assuming that productivity growth is about constant, then the trough of the recession represents a structural break and the economy would resume on its former trend from the new start point. Mathematically, I’m asking if there is a change in the intercept, while holding the slope of the regression more or less constant.

If the structural break as well as all the other variables are statistically significant, then I have proven my hypothesis that the Malaysian economy has moved to a permanently lower path of economic growth, and there has been a de facto loss in potential output. Bear in mind that we’re only looking at four quarters worth of data to work with i.e. from the point where the economy started growing again.

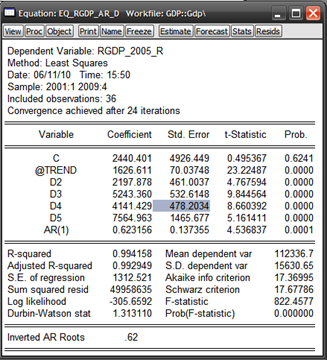

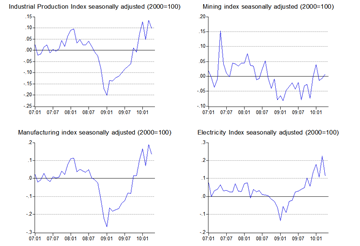

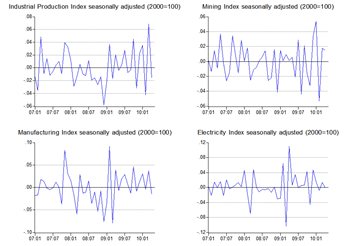

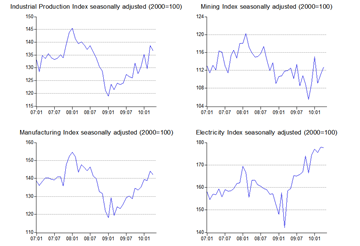

Defining d5 as the structural break variable, with values of 1 from 2001:1 to 2009:1, and zero thereafter, and rerunning the regressions with a larger sample range of 2001:1 to 2010:1, here are the results:

The results generated generally support my thesis – the economy has moved to a new path for economic growth, which in turn implies that there has indeed been a permanent loss in potential output.

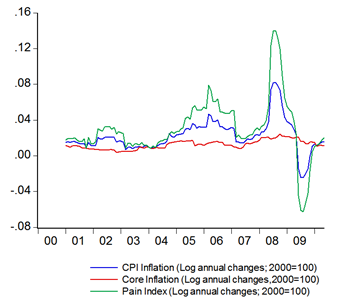

Now for a more normative approach – it’s hard to reconcile my results with the fact that for Malaysia at least, the genesis for the recession was external. There was nothing fundamentally wrong with the economy pre-crisis, pace NEAC and the NEM. If demand was to fully recover, then we should expect to see a “V” shaped recovery back to trend (just back to the pre-crisis level of output is not sufficient). That hasn’t happened here, obviously.

In that light what I think we’re seeing is, potentially, a permanent loss in external demand and not a permanent loss in the potential output capacity of the economy. That in itself will eventually result in the same thing (unused capacity will be depreciate away), but there’s always hope for a stronger recovery though I’m having trouble right now seeing where that might come from.

So what could happen in time is more like a “U” shaped recovery back to trend – I’m crossing my fingers we don’t see a “W”. But in the context of what I’ve done here in this post, we’ll have to wait and see.

Technical Notes:

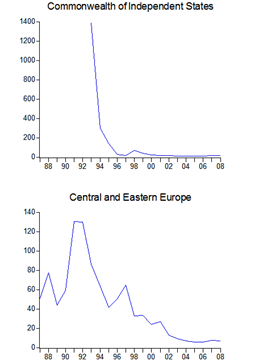

First graph and intellectual inspiration from:

Cerra, Valerie & Saxena, Sweta Chaman, "Did Output Recover from the Asian Crisis?", IMF Working Paper No. 03/48